All physical media comes with a digital download card

Lucy Liyou

Welfare / Practice

“I'm trying to document emotions, more than specific events and memories. I mean...that's what my music is at the end of the day - I'm just documenting.”

This is Lucy Liyou, the Philadelphia-based experimental musician behind cinematic sister LPs Welfare and Practice. Working in their Korean-American lineage and pulling from childhood memories, Liyou takes inspiration from Pansori (Korean Folk Opera), a style of Korean musical storytelling; and Korean drama soundtracks. Collaging text-to-speech (TTS) with their own voice, personal field recordings, audio samples from memes, Tumblr, and YouTube videos, synthesizers, and lush acoustic piano, Liyou creates their own distinct narrative.

Composition for Welfare began in late 2019, when Liyou set out to write an album inspired by Pansori recordings their grandfather used to play. Pansori is traditionally performed by a single vocalist accompanied by a drummer who plays a Korean drum called a buk. “It made me think about what storytelling is through music, and how powerful and world-building the voice alone can be,'' says Liyou. “I wanted to emulate that but in kind of a brutalized manner...so I was like, let's try it with the TTS.” Liyou did careful research into Pansori in the process of creating Welfare, wanting to be very deliberate in the record’s composition. They laugh, “I literally had a thesis for that album, I was almost out of my mind.”

The record begins with “I’m Going To Therapy”, a ten-and-a-half minute track that opens with a haunting “Happy Birthday” motif before snapping into focus on a clear voice asking, “When would be a good time to tell Mom I’m going to therapy?” The piece walks listeners through Liyou’s tumultuous experience of going to therapy for the first time, and navigating how to communicate about it with their family. “It's so taboo in a lot of Korean households,” they explain. Like much of Liyou’s music, Welfare is largely about family, identity, and the complicated dynamic between the artist and their parents.

“Unnie” is the second track on Welfare, and the most musically straightforward, with rich reverb-laden piano cradling Liyou’s own gentle singing voice. The song, which is sung half in Korean and half in English, touches on themes of gender identity and familial connection. Here, Liyou’s love of R&B can be faintly detected, as wispy ethereal backup vocals echo their slow, mellow voice repeating “But I’ll take it, but I’ll take it.” The track, which was written after the rest of Welfare, wasn’t originally supposed to be included in the album. It wasn’t until ijn inc. label-head Klein heard the track and suggested they add it that “Unnie” became part of the album. Liyou jokes that now the track is everybody’s favorite off the record.

On “Who You Feed” Liyou jolts listeners from the serene comfort of “Unnie” to a darker, noisier, at times dance-inspired sonic fabric. The track was made with help of friend and electronic musician Barbara Bonita, who collaborated with Liyou on the harsher, noisier elements of the piece. The track ends with a minute-long field recording of pigs snorting as ambient voices linger in the background. Liyou describes it as being like a fairy tale, a fantastical mood similar to that of Pansori, posing the question of how much one owes their parents, and playing off themes of guilt and expectation.

In the record’s closing track, “Some Form of Kindness”, Liyou moves through melancholic vignettes in an ending more contemplative and synth-focused than other tracks. “I love you, I love you,” repeats a soft, childlike voice throughout the album's final piece, as different melodic lines drift in and out with metallic shards and pieces of stories seething in the environs. More questions are asked but seldom answered at the center of the silhouette: “I love you, I love you, I love you…” “…then why do you hold me like an enemy?”

–

“I was not even really planning to make [Practice], it just kind of happened. I kind of made it as therapy work for myself.”

Unlike the deliberate, planned out Welfare, Lucy Liyou’s 2021 follow-up Practice was composed and recorded entirely within a two-week period early in the Covid-19 pandemic, while the artist was living at their parents’ home in Seattle. When Liyou’s elderly grandmother became ill, their mother flew to Korea to be with her. Due to pandemic restrictions, Liyou’s mother had to undergo a two-week quarantine in isolation upon landing in Korea. “Life felt ridiculously stagnant and very depressing overall,” says Liyou of the waiting period. “We were scared. I think the biggest fear amongst the family was that my mom was not even going to get to see my grandma before she passed.”

Home in Seattle, Liyou didn’t have access to much of their gear, like the MIDI keyboard and recording equipment used to make Welfare. So they worked with what they had—namely, an acoustic piano, recorded in single takes via their iPhone. The return to piano was natural for Liyou; the artist grew up playing classical piano competitively from an early age.

The record moves through tracks in the chronological order that they were made, beginning with the day their mother left for Korea. In the opening track, “You Are Every Memory”, Liyou kicks the album off with lush, sentimental piano. “I was inspired by Korean drama soundtracks,” Liyou explains. “I love how corny Korean drama soundtracks are because it's beautiful. I don't care what anyone says, corny is beautiful!”

Most of the songs on Practice are around three minutes long, in contrast with the longer form tracks on Welfare. In “Uncle” and “At the Dinner Table”, Liyou revisits Pansori methodology through TTS to tell vivid stories of family and frustration. The second half of “Easiest” delivers nearly three straight minutes of piano improvisation over the low rumbling whirring of wind.

“How to Build an Automaton” and “Patron” are darker, synthier pieces, more reminiscent of the sounds found on Welfare. There is an invisible motion at play in Practice, a traversal across different sonic environments guided by visceral field recordings like the slamming of silverware on the table or the ambient sounds of an airport. Liyou expertly breaks out of familiar field recording tropes, using found sounds almost like the soundtrack to a film.

“September 5” marks the day Liyou’s mother got out of quarantine, and the album’s final track. “I knew it was the end,” Lucy recalls of recording the song, “a weight was lifted because I knew my mom was there with my grandmother.” The lyrics explain that despite the occurrence of a typhoon the day their mother left quarantine, it remained a beautiful day because the waiting was finally over. It is here, in the finale of an LP that digs deep into family tension and unease, that Liyou leaves listeners with a message of love, joy, and connection.

“Grandma, you bought me a piano when I was 5, it was an electric Yamaha,” Liyou softly recounts over an exquisite piano melody. “Do you remember that one time we watched a Korean drama together? You had cut up some strawberries, poured yourself some instant coffee, and asked if I could play the show’s original soundtrack. And I said ‘no, not yet, Grandma. But I’ll practice. I’ll practice every day.’ And you looked at me, laughed, and gave me my favorite embrace.”

released May 20, 2022

Remastered by Andrew Weathers

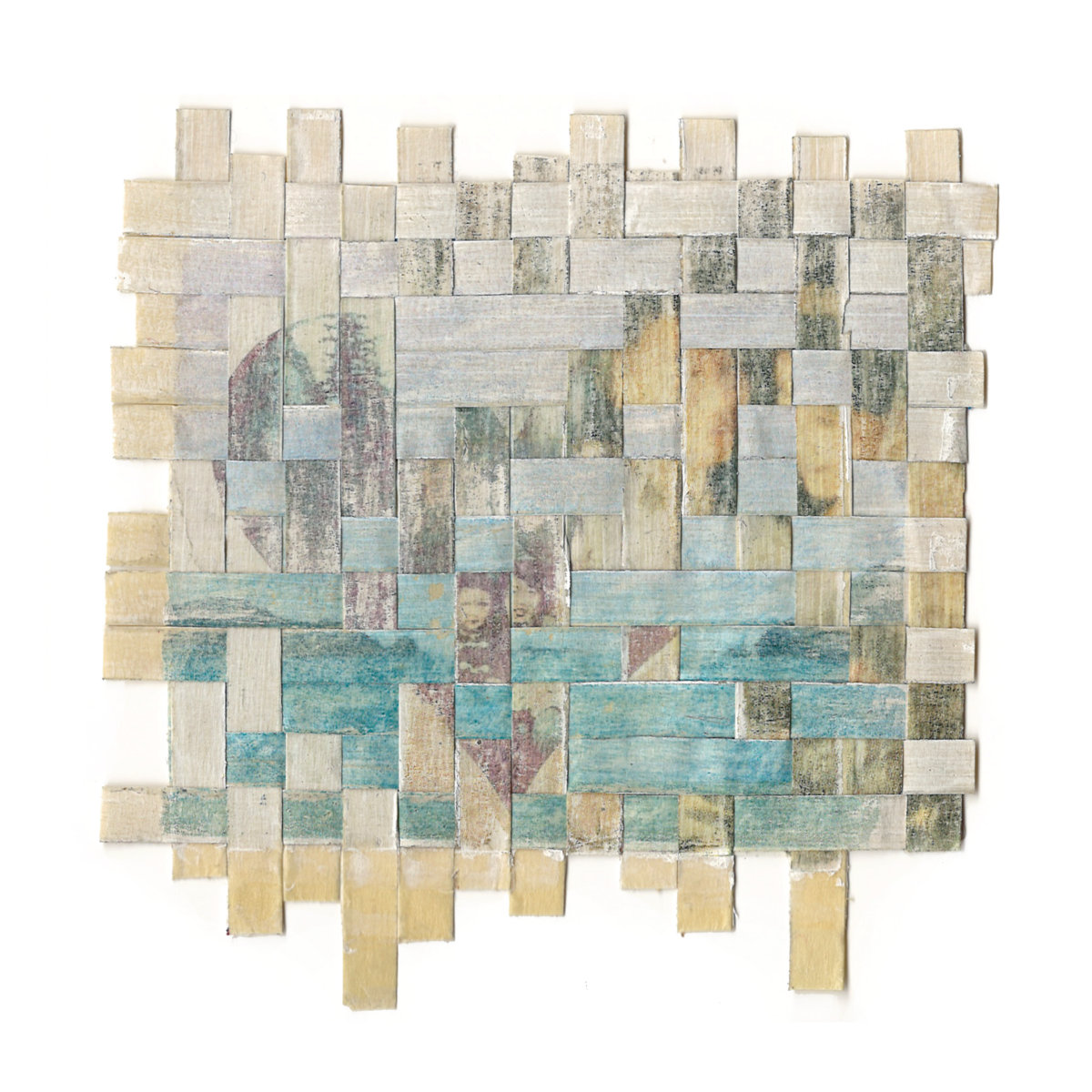

Album Design by Devin Shaffer

Album Art by Wilson Minshall

Original Art on Practice by Wilson Minshall

Original Art on Welfare by Faye Wei Wei